From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Tree (disambiguation).

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, supporting branches and leaves in most species. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are usable as lumber or plants above a specified height. Trees are not a taxonomic group but include a variety of plant species that have independently evolved a woody trunk and branches as a way to tower above other plants to compete for sunlight. In looser senses, the taller palms, the tree ferns, bananas and bamboos are also trees. Trees tend to be long-lived, some reaching several thousand years old. The tallest known tree, a coast redwood named Hyperion, stands 115.6 m (379 ft) high. Trees have been in existence for 370 million years. It is estimated that there are just over 3 trillion mature trees in the world.[1]

A tree typically has many secondary branches supported clear of the ground by the trunk. This trunk typically contains woody tissue for strength, and vascular tissue to carry materials from one part of the tree to another. For most trees it is surrounded by a layer of bark which serves as a protective barrier. Below the ground, the roots branch and spread out widely; they serve to anchor the tree and extract moisture and nutrients from the soil. Above ground, the branches divide into smaller branches and shoots. The shoots typically bear leaves, which capture light energy and convert it into sugars by photosynthesis, providing the food for the tree's growth and development. Flowers and fruit may also be present, but some trees, such as conifers, instead have pollen cones and seed cones; others, such as tree ferns, produce spores instead.

Trees play a significant role in reducing erosion and moderating the climate. They remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store large quantities of carbon in their tissues. Trees and forests provide a habitat for many species of animals and plants. Tropical rainforests are one of the most biodiverse habitats in the world. Trees provide shade and shelter, timber for construction, fuel for cooking and heating, and fruit for food as well as having many other uses. In parts of the world, forests are shrinking as trees are cleared to increase the amount of land available for agriculture. Because of their longevity and usefulness, trees have always been revered, with sacred groves in various cultures, and they play a role in many of the world's mythologies.

Contents

[show]

Definition

Although "tree" is a term of common parlance, there is no universally recognised precise definition of what a tree is, either botanically or in common language.[2] In its broadest sense, a tree is any plant with the general form of an elongated stem, or trunk, which supports the photosynthetic leaves or branches at some distance above the ground.[3] Trees are also typically defined by height,[4] with smaller plants from 0.5 to 10 m (1.6 to 32.8 ft) being called shrubs,[5] so the minimum height of a tree is only loosely defined.[4] Large herbaceous plants such as papaya and bananas are trees in this broad sense.[2][6]

A commonly applied narrower definition is that a tree has a woody trunk formed by secondary growth, meaning that the trunk thickens each year by growing outwards, in addition to the primary upwards growth from the growing tip.[4][7] Under such a definition, herbaceous plants such as palms, bananas and papayas are not considered trees regardless of their height, growth form or stem girth. Certain monocots may be considered trees under a slightly looser definition;[8] while the Joshua tree, bamboos and palms do not have secondary growth and never produce true wood with growth rings,[9][10] they may produce "pseudo-wood" by lignifying cells formed by primary growth.[11]

Aside from structural definitions, trees are commonly defined by use, for instance as those plants which yield lumber.[12]

Overview

The tree growth habit is an evolutionary adaptation found in different groups of plants: by growing taller, trees are able to compete better for sunlight.[13] Trees tend to be long-lived,[14] some reaching several thousand years old, as well as tall.[15] Trees have modified structures such as thicker stems composed of specialised cells that add structural strength and durability, allowing them to grow taller than non-woody plants and to spread out their foliage. They differ from shrubs, which are also woody plants, by usually growing larger and having a single main stem;[5] but the distinction between a small tree and a large shrub is not always clear,[16] made more confusing by the fact that trees may be reduced in size under harsher environmental conditions such as on mountains and subarctic areas. The tree form has evolved separately in unrelated classes of plants in response to similar environmental challenges, making it a classic example of parallel evolution. With an estimated 100,000 species, the number of trees worldwide might total twenty-five per cent of all living plant species.[17] The greatest number of these grow in tropical regions and many of these areas have not yet been fully surveyed by botanists, making tree diversity and ranges poorly known.[18]

Trees exist in two different groups of vascular or higher plants, the gymnosperms and the angiosperms. The gymnosperm trees include conifers, cycads, ginkgophytes and gnetales; they produce seeds which are not enclosed in fruits, but in open structures such as pine cones, and many have tough waxy leaves, such as pine needles.[19] Most angiosperm trees are eudicots, the "true dicotyledons", so named because the seeds contain two cotyledons or seed leaves. There are also some trees among the old lineages of flowering plants called basal angiosperms or paleodicots; these include Amborella, Magnolia, nutmeg and avocado,[20] while trees such as bamboo, palms and bananas are monocots.

Wood gives structural strength to the trunk of a tree; this supports the plant as it grows larger. The vascular system of trees allows water, nutrients and other chemicals to be distributed around the plant, and without it trees would not be able to grow as large as they do. Trees, as relatively tall plants, need to draw water up the stem through the xylem from the roots by the suction produced as water evaporates from the leaves. If insufficient water is available the leaves will die.[21] The three main parts of trees include the root, stem, and leaves; they are integral parts of the vascular system which interconnects all the living cells. In trees and other plants that develop wood, the vascular cambium allows the expansion of vascular tissue that produces woody growth. Because this growth ruptures the epidermis of the stem, woody plants also have a cork cambium that develops among the phloem. The cork cambium gives rise to thickened cork cells to protect the surface of the plant and reduce water loss. Both the production of wood and the production of cork are forms of secondary growth.[22]

Trees are either evergreen, having foliage that persists and remains green throughout the year,[23] or deciduous, shedding their leaves at the end of the growing season and then having a dormant period without foliage.[24] Most conifers are evergreens but larches (Larix and Pseudolarix) are deciduous, dropping their needles each autumn, and some species of cypress (Glyptostrobus, Metasequoia and Taxodium) shed small leafy shoots annually in a process known as cladoptosis.[5] The crown is a name for the spreading top of a tree including the branches and leaves,[25] while the uppermost layer in a forest, formed by the crowns of the trees, is known as the canopy.[26]A sapling is a young tree.[27]

Many tall palms are herbaceous[28] monocots; these do not undergo secondary growth and never produce wood.[9][10] In many tall palms, the terminal bud on the main stem is the only one to develop, so they have unbranched trunks with large spirally arranged leaves. Some of the tree ferns, order Cyatheales, have tall straight trunks, growing up to 20 metres (66 ft), but these are composed not of wood but of rhizomes which grow vertically and are covered by numerous adventitious roots.[29]

Distribution

Further information: Forest

The number of trees in the world, according to a 2015 estimate, is 3.04 trillion, of which 1.39 trillion (46%) are in the tropics or sub-tropics, 0.61 trillion (20%) in the temperate zones, and 0.74 trillion (24%) in the coniferous boreal forests. The estimate is about eight times higher than previous estimates, and is based on tree densities measured on over 400,000 plots. It remains subject to a wide margin of error, not least because the samples are mainly from Europe and North America. The estimate suggests that about 15 billion trees are cut down annually and about 5 billion are planted. In the 12,000 years since the start of human agriculture, the number of trees worldwide has decreased by 46%.[1][30][31][32]

In suitable environments, such as the Daintree Rainforest in Queensland, or the mixed podocarp and broadleaf forest of Ulva Island, New Zealand, forest is the more-or-less stable climatic climax community at the end of a plant succession, where open areas such as grassland are colonised by taller plants, which in turn give way to trees that eventually form a forest canopy.[33][34]

In cool temperate regions, conifers often predominate; a widely distributed climax community in the far north of the northern hemisphere is moist taiga or northern coniferous forest (also called boreal forest).[35][36] Taiga is the world's largest land biome, forming 29% of the world's forest cover.[37] The long cold winter of the far north is unsuitable for plant growth and trees must grow rapidly in the short summer season when the temperature rises and the days are long. Light is very limited under their dense cover and there may be little plant life on the forest floor, although fungi may abound.[38] Similar woodland is found on mountains where the altitude causes the average temperature to be lower thus reducing the length of the growing season.[39]

Where rainfall is relatively evenly spread across the seasons in temperate regions, temperate broadleaf and mixed forest typified by species like oak, beech, birch and maple is found.[40] Temperate forest is also found in the southern hemisphere, as for example in the Eastern Australia temperate forest, characterised by Eucalyptus forest and open acacia woodland.[41]

In tropical regions with a monsoon or monsoon-like climate, where a drier part of the year alternates with a wet period as in the Amazon rainforest, different species of broad-leaved trees dominate the forest, some of them being deciduous.[42] In tropical regions with a drier savanna climate and insufficient rainfall to support dense forests, the canopy is not closed, and plenty of sunshine reaches the ground which is covered with grass and scrub. Acacia and baobab are well adapted to living in such areas.[43]

Parts and function

Roots

Main article: Root

The roots of a tree serve to anchor it to the ground and gather water and nutrients to transfer to all parts of the tree. They are also used for reproduction, defence, survival, energy storage and many other purposes. The radicle or embryonic root is the first part of a seedling to emerge from the seed during the process of germination. This develops into a taproot which goes straight downwards. Within a few weeks lateral roots branch out of the side of this and grow horizontally through the upper layers of the soil. In most trees, the taproot eventually withers away and the wide-spreading laterals remain. Near the tip of the finer roots are single cell root hairs. These are in immediate contact with the soil particles and can absorb water and nutrients such as potassium in solution. The roots require oxygen to respire and only a few species such as the mangrove and the pond cypress (Taxodium ascendens) can live in permanently waterlogged soil.[44]

In the soil, the roots encounter the hyphae of fungi. Many of these are known as mycorrhiza and form a mutualistic relationship with the tree roots. Some are specific to a single tree species, which will not flourish in the absence of its mycorrhizal associate. Others are generalists and associate with many species. The tree acquires minerals such as phosphorus from the fungus while it obtains the carbohydrate products of photosynthesis from the tree.[45] The hyphae of the fungus can link different trees and a network is formed, transferring nutrients from one place to another. The fungus promotes growth of the roots and helps protect the trees against predators and pathogens. It can also limit damage done to a tree by pollution as the fungus accumulate heavy metals within its tissues.[46]Fossil evidence shows that roots have been associated with mycorrhizal fungi since the early Paleozoic, four hundred million years ago, when the first vascular plants colonised dry land.[47]

Some trees such as the alders (Alnus species) have a symbiotic relationship with Frankia species, a filamentous bacterium that can fix nitrogen from the air, converting it into ammonia. They have actinorhizal root nodules on their roots in which the bacteria live. This process enables the tree to live in low nitrogen habitats where they would otherwise be unable to thrive.[48] The plant hormones called cytokinins initiate root nodule formation, in a process closely related to mycorrhizal association.[49]

It has been demonstrated that some trees are interconnected through their root system, forming a colony. The interconnections are made by the inosculation process, a kind of natural grafting or welding of vegetal tissues. The tests to demonstrate this networking are performed by injecting chemicals, sometimes radioactive, into a tree, and then checking for its presence in neighbouring trees.[50]

The roots are, generally, an underground part of the tree, but some tree species have evolved roots that are aerial. The common purposes for aerial roots may be of two kinds, to contribute to the mechanical stability of the tree, and to obtain oxygen from air. An instance of mechanical stability enhancement is the red mangrove that develops prop roots that loop out of the trunk and branches and descend vertically into the mud.[51] A similar structure is developed by the Indian banyan.[52] Many large trees have buttress roots which flare out from the lower part of the trunk. These brace the tree rather like angle brackets and provide stability, reducing sway in high winds. They are particularly prevalent in tropical rainforests where the soil is poor and the roots are close to the surface.[53]

Some tree species have developed root extensions that pop out of soil, in order to get oxygen, when it is not available in the soil because of excess water. These root extensions are called pneumatophores, and are present, among others, in black mangrove and pond cypress.[51]

Trunk

Main article: Trunk (botany)

The main purpose of the trunk is to raise the leaves above the ground, enabling the tree to reach the light and survive: the tree can overtop other plants and shade them out. It also performs the task of transporting water and nutrients from the roots to the aerial parts of the tree and to distribute the food produced by the leaves to all other parts including the roots.[54]

In the case of angiosperms and gymnosperms, the outermost layer of the trunk is the bark and is mostly composed of dead cells. It provides a thick, waterproof covering to the living inner tissue. It protects the trunk against the elements, disease, animal attack and fire. It is perforated by a large number of fine breathing pores called lenticels, through which oxygen diffuses. Bark is continually replaced by a living layer of cells called the cork cambium. The London plane (Platanus × acerifolia) periodically sheds its bark in large flakes. Similarly, the bark of the silver birch (Betula pendula) peels off in strips. As the tree's girth expands, newer layers of bark are larger in circumference, and the older layers develop fissures in many species. In some trees such as the pine (Pinus species) the bark exudes sticky resin which deters attackers whereas in rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) it is a milky latex that oozes out. The quinine bark tree (Cinchona officinalis) contains bitter substances to make the bark unpalatable.[54] Large tree-like plants with lignified trunks in the Pteridophyta, Arecales, Cycadophyta and Poales such as the tree ferns, palms, cycads and bamboos have no true bark, but they do have an outer protective covering of some form.[55]

Although the bark functions as a protective barrier, it is itself attacked by boring insects such as beetles. These lay their eggs in crevices and the larvae chew their way through the cellulose tissues leaving a gallery of tunnels. This may allow fungal spores to gain admittance and attack the tree. Dutch elm disease is caused by a fungus (Ophiostoma species) carried from one elm tree to another by various beetles. The tree reacts to the growth of the fungus by blocking off the xylem tissue carrying sap upwards and the branch above, and eventually the whole tree, is deprived of nourishment and dies. In Britain in the 1990s, 25 million elm trees were killed by this disease.[56]

The innermost layer of bark is known as the phloem and this is involved in the transport of the sap containing the sugars made by photosynthesis to other parts of the tree. It is a soft spongy layer of living cells, some of which are arranged end to end to form tubes. These are supported by parenchyma cells which provide padding and include fibres for strengthening the tissue.[57] Inside the phloem is a layer of undifferentiated cells one cell thick called the vascular cambium layer. The cells are continually dividing, creating phloem cells on the outside and wood cells known as xylem on the inside.[58]

The newly created xylem is the sapwood. It is composed of water-conducting cells and associated cells which are often living, and is usually pale in colour. It transports water and minerals from the roots to the upper parts of the tree. The oldest, inner part of the sapwood is progressively converted into heartwood as new sapwood is formed at the cambium. The conductive cells of the heartwood are blocked in some species, and the surrounding cells are more often dead. Heartwood is usually darker in colour than the sapwood. It is the dense central core of the trunk giving it rigidity. Three quarters of the dry mass of the xylem is cellulose, a polysaccharide, and most of the remainder is lignin, a complex polymer. A transverse section through a tree trunk or a horizontal core will show concentric circles or lighter or darker wood - tree rings. These rings are the annual growth rings[59] There may also be rays running at right angles to growth rings. These are vascular rays which are thin sheets of living tissue permeating the wood.[60] Many older trees may become hollow but may still stand upright for many years.[61]

Buds and growth

Main article: Bud

Trees do not usually grow continuously throughout the year but mostly have spurts of active expansion followed by periods of rest. This pattern of growth is related to climatic conditions; growth normally ceases when conditions are either too cold or too dry. In readiness for the inactive period, trees form buds to protect the meristem, the zone of active growth. Before the period of dormancy, the last few leaves produced at the tip of a twig form scales. These are thick, small and closely wrapped and enclose the growing point in a waterproof sheath. Inside this bud there is a rudimentary stalk and neatly folded miniature leaves, ready to expand when the next growing season arrives. Buds also form in the axils of the leaves ready to produce new side shoots. A few trees, such as the eucalyptus, have "naked buds" with no protective scales and some conifers, such as the Lawson's cypress, have no buds but instead have little pockets of meristem concealed among the scale-like leaves.[62]

When growing conditions improve, such as the arrival of warmer weather and the longer days associated with spring in temperate regions, growth starts again. The expanding shoot pushes its way out, shedding the scales in the process. These leave behind scars on the surface of the twig. The whole year's growth may take place in just a few weeks. The new stem is unlignified at first and may be green and downy. The Arecaceae (palms) have their leaves spirally arranged on an unbranched trunk.[62] In some tree species in temperate climates, a second spurt of growth, a Lammas growth may occur which is believed to be a strategy to compensate for loss of early foliage to insect predators.[63]

Primary growth is the elongation of the stems and roots. Secondary growth consists of a progressive thickening and strengthening of the tissues as the outer layer of the epidermis is converted into bark and the cambium layer creates new phloem and xylem cells. The bark is inelastic.[64] Eventually the growth of a tree slows down and stops and it gets no taller. If damage occurs the tree may in time become hollow.[65]

Leaves

Main article: Leaf

Leaves are structures specialised for photosynthesis and are arranged on the tree in such a way as to maximise their exposure to light without shading each other. They are an important investment by the tree and may be thorny or contain phytoliths, lignins, tannins or poisons to discourage herbivory. Trees have evolved leaves in a wide range of shapes and sizes, in response to environmental pressures including climate and predation. They can be broad or needle-like, simple or compound, lobed or entire, smooth or hairy, delicate or tough, deciduous or evergreen. The needles of coniferous trees are compact but are structurally similar to those of broad-leaved trees. They are adapted for life in environments where resources are low or water is scarce. Frozen ground may limit water availability and conifers are often found in colder places at higher altitudes and higher latitudes than broad leaved trees. In conifers such as fir trees, the branches hang down at an angle to the trunk, enabling them to shed snow. In contrast, broad leaved trees in temperate regions deal with winter weather by shedding their leaves. When the days get shorter and the temperature begins to decrease, the leaves no longer make new chlorophyll and the red and yellow pigments already present in the blades become apparent.[66] Synthesis in the leaf of a plant hormone called auxin also ceases. This causes the cells at the junction of the petiole and the twig to weaken until the joint breaks and the leaf floats to the ground. In tropical and subtropical regions, many trees keep their leaves all year round. Individual leaves may fall intermittently and be replaced by new growth but most leaves remain intact for some time. Other tropical species and those in arid regions may shed all their leaves annually, such as at the start of the dry season.[67] Many deciduous trees flower before the new leaves emerge.[68] A few trees do not have true leaves but instead have structures with similar external appearance such as Phylloclades – modified stem structures[69] – as seen in the genus Phyllocladus.[70]

Reproduction

Main article: Plant reproduction

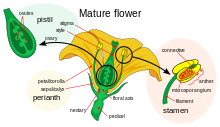

Tree forms are found in a wide range of plants and their reproductive strategies are substantially the same as shrub or herbaceous plant forms. Many trees are wind pollinated which may be an evolutionary adaptation to take advantage of increased wind speeds high above the ground, particularly in the case of those that produce pollen before the leaves emerge.[71] A vast quantity of pollen is produced because of the low likelihood of any particular grain landing on an appropriate female flower. Wind-pollinated flowers of broad-leaved trees are characterised by a lack of showy parts, no scent and a copious production of pollen, often with separate male and female flowers, or separate male and female trees. The male flowers may be high up in the tree, often in the form of dangling catkins. The female flowers may be lower down the tree. The pollen of pine trees contains air sacs which give it buoyancy and it has been known to travel as far as 800 kilometres (500 mi).[72] Tree pollen can cause allergies and hay fever.[73]

Seeds

Main article: Seed

Seeds are the primary way that trees reproduce and their seeds vary greatly in size and shape. Some of the largest seeds come from trees, but the largest tree, Sequoiadendron giganteum, produces one of the smallest tree seeds.[74] The great diversity in tree fruits and seeds reflects the many different ways that tree species have evolved to disperse their offspring.

The single extant species of Ginkgophyta (Ginkgo biloba) has fleshy seeds produced at the ends of short branches on female trees,[75] and Gnetum, a tropical and subtropical group of gymnosperms produce seeds at the tip of a shoot axis.[76] The seeds of conifers, the largest group of gymnosperms, are enclosed in a cone and most species have seeds that are light and papery that can be blown considerable distances once free from the cone.[77] Sometimes the seed remains in the cone for years waiting for a trigger event to liberate it. Fire stimulates release and germination of seeds of the jack pine, and also enriches the forest floor with wood ash and removes competing vegetation.[78] Similarly, a number of angiosperms including Acacia cyclops and Acacia mangium have seeds that germinate better after exposure to high temperatures.[79]

For a tree seedling to grow into an adult tree it needs light and space. If seeds only fell straight to the ground, competition among the concentrated saplings and the shade of the parent would likely prevent it from flourishing. Many seeds such as birch are small and have papery wings to aid dispersal by the wind. Ash trees and maples have larger seeds with blade shaped wings which spiral down to the ground when released. The kapok tree has cottony threads to catch the breeze.[80] The flame tree does not rely on fire but shoots its seeds through the air when the two sides of its long pods crack apart explosively on drying.[80] The miniature cone-like catkins of Alder trees produce seeds that contain small droplets of oil that help disperse the seeds on the surface of water. Mangroves often grow in water and some species have propagules, which are buoyant fruits with seeds that start germinating before becoming detached from the parent tree.[81][82] These float on the water and may become lodged on emerging mudbanks and successfully take root.[80] Other seeds, such as apple pips and plum stones, have fleshy receptacles and smaller fruits like hawthorns have seeds enclosed in edible tissue; animals including mammals and birds eat the fruits and either discard the seeds, or swallow them so they pass through the gut to be deposited in the animal's droppings well away from the parent tree. The germination of some seeds is improved when they are processed in this way.[83] Nuts may be gathered by animals such as squirrels that cache any not immediately consumed.[84] Many of these caches are never revisited, the nut-casing softens with rain and frost, and the seed germinates in the spring.[85] Pine cones may similarly be hoarded by red squirrels, and grizzly bears may help to disperse the seed by raiding squirrel caches.[86]

Evolutionary history

Further information: Evolutionary history of plants

The earliest tree-like organisms were tree ferns, horsetails and lycophytes, which grew in forests in the Carboniferous period. The first tree may have been Wattieza, fossils of which have been found in New York State in 2007 dating back to the Middle Devonian (about 385 million years ago). Prior to this discovery, Archaeopteris was the earliest known tree.[87] Both of these reproduced by spores rather than seeds and are considered to be links between ferns and the gymnosperms which evolved in the Triassic period. The gymnosperms include conifers, cycads, gnetales and ginkgos and these may have appeared as a result of a whole genome duplication event which took place about 319 million years ago.[88] Ginkgophyta was once a widespread diverse group [89] of which the only survivor is the maidenhair tree Ginkgo biloba. This is considered to be a living fossil because it is virtually unchanged from the fossilised specimens found in Triassic deposits.[90]

During the Mesozoic (245 to 66 million years ago) the conifers flourished and became adapted to live in all the major terrestrial habitats. Subsequently, the tree forms of flowering plants evolved during the Cretaceous period. These began to dominate the conifers during the Tertiary era (66 to 2 million years ago) when forests covered the globe. When the climate cooled 1.5 million years ago and the first of four ice ages occurred, the forests retreated as the ice advanced. In the interglacials, trees recolonised the land that had been covered by ice, only to be driven back again in the next ice age.[91]

Tree ecology

Further information: Forest

Trees are an important part of the terrestrial ecosystem,[92] providing essential habitats including many kinds of forest for communities of organisms. Epiphytic plants such as ferns, some mosses, liverworts, orchids and some species of parasitic plants (e.g., mistletoe) hang from branches; these along with arboreal lichens, algae, and fungi provide micro-habitats for themselves and for other organisms, including animals. Leaves, flowers and fruits are seasonally available. On the ground underneath trees there is shade, and often there is undergrowth, leaf litter, fallen branches and/or decaying wood that provide other habitat. Trees stabilise the soil, prevent rapid run-off of rain water, help prevent desertification, have a role in climate control and help in the maintenance of biodiversity and ecosystem balance.[93]

Many species of tree support their own specialised invertebrates. In their natural habitats, 284 different species of insect have been found on the English oak (Quercus robur) [94]and 306 species of invertebrate on the Tasmanian oak (Eucalyptus obliqua).[95] Non-native tree species provide a less biodiverse community, for example in the United Kingdom the sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), which originates from southern Europe, has few associated invertebrate species, though its bark supports a wide range of lichens, bryophytes and other epiphytes.[96]

In ecosystems such as mangrove swamps, trees play a role in developing the habitat, since the roots of the mangrove trees reduce the speed of flow of tidal currents and trap water-borne sediment, reducing the water depth and creating suitable conditions for further mangrove colonisation. Thus mangrove swamps tend to extend seawards in suitable locations.[97] Mangrove swamps also provide an effective buffer against the more damaging effects of cyclones and tsunamis.[98]

Uses

Silviculture is the practice of controlling the establishment, growth, composition, health, and quality of forests, which are areas that have a high density of trees. Cultivated trees are planted and tended by humans, usually because they provide food (fruits or nuts), ornamental beauty, or some type of wood product that benefits people. A small wooded area, usually with no undergrowth, is called a grove [99] and a small wood or thicket of trees and bushes is called a coppice or copse.[100] A large area of land covered with trees and undergrowth is called woodland or forest.[101] An area of woodland composed primarily of trees established by planting or artificial seeding is known as a plantation [102] and an area of land planted with fruit or nut trees is an orchard.[103]

Food

Further information: nut (fruit) and fruit

Trees are the source of many of the world's best known fleshy fruits. Apples, pears, plums, cherries and citrus are all grown commercially in temperate climates and a wide range of edible fruits are found in the tropics. Other commercially important fruit include dates, figs and olives. Palm oil is obtained from the fruits of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis). The fruits of the cocoa tree (Theobroma cacao) are used to make cocoa and chocolate and the berries of coffee trees, Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora, are processed to extract the coffee beans. In many rural areas of the world, fruit is gathered from forest trees for consumption.[104] Many trees bear edible nuts which can loosely be described as being large, oily kernels found inside a hard shell. These include coconuts (Cocos nucifera), Brazil nuts (Bertholletia excelsa), pecans (Carya illinoinensis), hazel nuts (Corylus), almonds (Prunus dulcis), walnuts (Juglans regia), pistachios (Pistacia vera) and many others. They are high in nutritive value and contain high-quality protein, vitamins and minerals as well as dietary fibre. Walnuts are particularly beneficial to health and contain a higher level of antioxidants than do other nuts.[105] A variety of nut oils are extracted by pressing for culinary use; some such as walnut, pistachio and hazelnut oils are prized for their distinctive flavours, but they tend to spoil quickly.[106]

Many trees have flowers rich in nectar which are attractive to bees. The production of forest honey is an important industry in rural areas of the developing world where it is undertaken by small-scale beekeepers using traditional methods.[107] The flowers of the elder (Sambucus) are used to make elderflower cordial and petals of the plum (Prunus spp.) can be candied.[108]

The leaves of trees are widely gathered as fodder for livestock and some can be eaten by humans but they tend to be high in tannins which makes them bitter. Leaves of the curry tree (Murraya koenigii) are eaten, those of kaffir lime Citrus × hystrix (e.g., Thai food)[109] Ailanthus (e.g., in Korean dishes such as bugak) and those of the European bay tree (Laurus nobilis) and the California bay tree (Umbellularia californica) are used for flavouring food.[110] Camellia sinensis, the source of tea, is a small tree but seldom reaches its full height, being heavily pruned to make picking the leaves easier.[111]

In temperate climates there is a sudden movement of sap at the end of the winter as trees prepare to burst into growth. In North America, the sap of the sugar maple (Acer saccharum) is most often used in the production of a sweet liquid, maple syrup. About 90% of the sap is water, the remaining 10% being a mixture of various sugars and certain minerals.[112] The sap is harvested by drilling holes in the trunks of the trees and collecting the liquid that flows out of the inserted spigots. It is piped to a sugarhouse where it is heated to concentrate it and improve its flavour. One litre of maple syrup is obtained from every forty litres of sap and has a sugar content of exactly 66%.[112] Similarly in northern Europe the spring rise in the sap of the silver birch (Betula pendula) is tapped and collected, either to be drunk fresh or fermented into an alcoholic drink. In Alaska, the sap of the sweet birch (Betula lenta) is made into a syrup with a sugar content of 67%. Sweet birch sap is more dilute than maple sap; a hundred litres are required to make one litre of birch syrup.[113]

Various parts of trees are used as spices. These include cinnamon, made from the bark of the cinnamon tree (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) and allspice, the dried small fruits of the pimento tree (Pimenta dioica). Nutmeg is a seed found in the fleshy fruit of the nutmeg tree (Myristica fragrans) and cloves are the unopened flower buds of the clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum). Sassafras oil is an important flavouring obtained from distilling bark from the roots of the white sassafras tree (Sassafras albidum).[110]

Fuel

Main article: Wood fuel

Wood has traditionally been used for fuel, especially in rural areas. In less developed nations it may be the only fuel available and collecting firewood is often a time consuming task as it becomes necessary to travel further and further afield in the search for fuel.[114] It is often burned inefficiently on an open fire. In more developed countries other fuels are available and burning wood is a choice rather than a necessity. Modern wood-burning stoves are very fuel efficient and new products such as wood pellets are available to burn.[115]

Charcoal can be made by slow pyrolysis of wood by heating it in the absence of air in a kiln. The carefully stacked branches, often oak, are burned with a very limited amount of air. The process of converting them into charcoal takes about fifteen hours. Charcoal is used as a fuel in barbecues and by blacksmiths and has many industrial and other uses.[116]

Wood smoke can be used to preserve food. In the hot smoking process the food is exposed to smoke and heat in a controlled environment. The food is ready to eat when the process is complete, having been tenderised and flavoured by the smoke it has absorbed. In the cold process, the temperature is not allowed to rise above 100 °F (38 °C). The flavour of the food is enhanced but raw food requires further cooking. If it is to be preserved, meat should be cured before cold smoking.[117]

Timber

Timber, "trees that are grown in order to produce wood"[118] is cut into lumber (sawn wood) for use in construction. Wood has been an important, easily available material for construction since humans started building shelters. Engineered wood products are available which bind the particles, fibres or veneers of wood together with adhesives to form composite materials. Plastics have taken over from wood for some traditional uses.[119]

Wood is used in the construction of buildings, bridges, trackways, piles, poles for power lines, masts for boats, pit props, railway sleepers, fencing, hurdles, shuttering for concrete, pipes, scaffolding and pallets. In housebuilding it is used in joinery, for making joists, roof trusses, roofing shingles, thatching, staircases, doors, window frames, floor boards, parquet flooring, panelling and cladding.[120]

Wood is used to construct carts, farm implements, boats, dugout canoes and in shipbuilding. It is used for making furniture, tool handles, boxes, ladders, musical instruments, bows, weapons, matches, clothes pegs, brooms, shoes, baskets, turnery, carving, toys, pencils, rollers, cogs, wooden screws, barrels, coffins, skittles, veneers, artificial limbs, oars, skis, wooden spoons, sports equipment and wooden balls.[120]

Wood is pulped for paper and used in the manufacture of cardboard and made into engineered wood products for use in construction such as fibreboard, hardboard, chipboard and plywood.[120] The wood of conifers is known as softwood while that of broad-leaved trees is hardwood.[121]

Art

Besides inspiring artists down the centuries, trees have been used to create art. Living trees have been used in bonsai and in tree shaping, and both living and dead specimens have been sculpted into sometimes fantastic shapes.[122]

Bonsai

Main article: Bonsai

Bonsai (盆 栽?, lit. The art of growing a miniature tree or trees in a low-sided pot or tray) is the practice of hòn non bộ originated in China and spread to Japan more than a thousand years ago, there are similar practices in other cultures like the living miniature landscapes of Vietnam hòn non bộ. The word bonsai is often used in English as an umbrella term for all miniature trees in containers or pots.[123]

The purposes of bonsai are primarily contemplation (for the viewer) and the pleasant exercise of effort and ingenuity (for the grower).[124] Bonsai practice focuses on long-term cultivation and shaping of one or more small trees growing in a container, beginning with a cutting, seedling, or small tree of a species suitable for bonsai development. Bonsai can be created from nearly any perennial woody-stemmed tree or shrub species[125] that produces true branches and can be cultivated to remain small through pot confinement with crown and root pruning. Some species are popular as bonsai material because they have characteristics, such as small leaves or needles, that make them appropriate for the compact visual scope of bonsai and a miniature deciduous forest can even be created using such species as Japanese maple, Japanese zelkova or hornbeam.[126]

Tree shaping

Main article: Tree shaping

Tree shaping is the practice of changing living trees and other woody plants into man made shapes for art and useful structures. There are a few different methods [127] of shaping a tree. There is a gradual method and there is an instant method, the gradual method slowly guides the growing tip along predetermined path ways over time where as the instant method bends and weaves saplings 2 to 3 m (6.6 to 9.8 ft) long into a shape that becomes more rigid as they thicken up.[128] Most artists use grafting of living trunks, branches, and roots, for art or functional structures and there are plans to grow "living houses" with the branches of trees knitting together to give a solid, weatherproof exterior combined with an interior application of straw and clay to provide a stucco-like inner surface.[128]

Tree shaping has been practised for at least several hundred years, the oldest known examples being the living root bridges built and maintained by the Khasi people of Meghalaya, India using the roots of the rubber tree (Ficus elastica).[129][130]

Bark

Cork is produced from the thick bark of the cork oak (Quercus suber). It is harvested from the living trees about once every ten years in an environmentally sustainable industry.[131] More than half the world's cork comes from Portugal and is largely used to make stoppers for wine bottles.[132] Other uses include floor tiles, bulletin boards, balls, footwear, cigarette tips, packaging, insulation and joints in woodwind instruments.[132]

The bark of other varieties of oak has traditionally been used in Europe for the tanning of hides though bark from other species of tree has been used elsewhere. The active ingredient, tannin, is extracted and after various preliminary treatments, the skins are immersed in a series of vats containing solutions in increasing concentrations. The tannin causes the hide to become supple, less affected by water and more resistant to bacterial attack.[133]

At least 120 drugs come from plant sources, many of them from the bark of trees.[134] Quinine originates from the cinchona tree (Cinchona) and was for a long time the remedy of choice for the treatment of malaria.[135] Aspirin was synthesised to replace the sodium salicylate derived from the bark of willow trees (Salix) which had unpleasant side effects.[136] The anti-cancer drug Paclitaxel is derived from taxol, a substance found in the bark of the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia).[137] Other tree based drugs come from the paw-paw (Carica papaya), the cassia (Cassia spp.), the cocoa tree (Theobroma cacao), the tree of life (Camptotheca acuminata) and the downy birch (Betula pubescens).[134]

The papery bark of the white birch tree (Betula papyrifera) was used extensively by Native Americans. Wigwams were covered by it and canoes were constructed from it. Other uses included food containers, hunting and fishing equipment, musical instruments, toys and sledges.[138] Nowadays, bark chips, a by-product of the timber industry, are used as a mulch and as a growing medium for epiphytic plants that need a soil-free compost.[139]

Ornamental trees

Main articles: Forestry and Ornamental trees

Trees create a visual impact in the same way as do other landscape features and give a sense of maturity and permanence to park and garden. They are grown for the beauty of their forms, their foliage, flowers, fruit and bark and their siting is of major importance in creating a landscape. They can be grouped informally, often surrounded by plantings of bulbs, laid out in stately avenues or used as specimen trees. As living things, their appearance changes with the season and from year to year.[140]

Trees are often planted in town environments where they are known as street trees or amenity trees. They can provide shade and cooling through evapotranspiration, absorb greenhouse gasses and pollutants, intercept rainfall and reduce the risk of flooding. It has been shown that they are beneficial to humans in creating a sense of well-being and reducing stress. Many towns have initiated tree-planting programmes.[141] In London for example, there is an initiative to plant 20,000 new street trees and to have an increase in tree cover of 5% by 2025, equivalent to one tree for every resident.[142]

Other uses

Latex is a sticky defensive secretion that protects plants against herbivores. Many trees produce it when injured but the main source of the latex used to make natural rubber is the Pará rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Originally used to create bouncy balls and for the waterproofing of cloth, natural rubber is now mainly used in tyres for which synthetic materials have proved less durable.[143] The latex exuded by the balatá tree (Manilkara bidentata) is used to make golf balls and is similar to gutta-percha, made from the latex of the "getah perca" tree Palaquium. This is also used as an insulator, particularly of undersea cables, and in dentistry, walking sticks and gun butts. It has now largely been replaced by synthetic materials.[144]

Resin is another plant exudate that may have a defensive purpose. It is a viscous liquid composed mainly of volatile terpenes and is produced mostly by coniferous trees. It is used in varnishes, for making small castings and in ten-pin bowling balls. When heated, the terpenes are driven off and the remaining product is called "rosin" and is used by stringed instrumentalists on their bows. Some resins contain essential oils and are used in incense and aromatherapy. Fossilised resin is known as amber and was mostly formed in the Cretaceous (145 to 66 million years ago) or more recently. The resin that oozed out of trees sometimes trapped insects or spiders and these are still visible in the interior of the amber.[145]

The camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora) produces an essential oil [110] and the eucalyptus tree (Eucalyptus globulus) is the main source of eucalyptus oil which is used in medicine, as a fragrance and in industry.[146]

Care

Dead trees pose a safety risk, especially during high winds and severe storms, and removing dead trees involves a financial burden, whereas the presence of healthy trees can clean the air, increase property values, and reduce the temperature of the built environment and thereby reduce building cooling costs. During times of drought, trees can fall into water stress, which may cause a tree to become more susceptible to disease and insect problems, and ultimately may lead to a tree's death. Irrigating trees during dry periods can reduce the risk of water stress and death. Irrigation can be accomplished by use of a garden hose, soaker hose, sprinkler, or modified five-gallon bucket.[147]

Mythology

Main article: Tree worship

Trees have been venerated since time immemorial. To the ancient Celts, certain trees, especially the oak, ash and thorn, held special significance[148] as providing fuel, building materials, ornamental objects and weaponry. Other cultures have similarly revered trees, often linking the lives and fortunes of individuals to them or using them as oracles. In Greek mythology, dryads were believed to be shy nymphs who inhabited trees.

The Oubangui people of west Africa plant a tree when a child is born. As the tree flourishes, so does the child but if the tree fails to thrive, the health of the child is considered at risk. When it flowers it is time for marriage. Gifts are left at the tree periodically and when the individual dies, their spirit is believed to live on in the tree.[149]

Trees have their roots in the ground and their trunk and branches extended towards the sky. This concept is found in many of the world's religions as a tree which links the underworld and the earth and holds up the heavens. In Norse mythology, Yggdrasil is a central cosmic tree whose roots and branches extend to various worlds. Various creatures live on it.[150] In India, Kalpavriksha is a wish-fulfilling tree, one of the nine jewels that emerged from the primitive ocean. Icons are placed beneath it to be worshipped, tree nymphs inhabit the branches and it grants favours to the devout who tie threads round the trunk.[151] Democracy started in North America when the Great Peacemaker formed the Iroquois Confederacy, inspiring the warriors of the original five American nations to bury their weapons under the Tree of Peace, an eastern white pine (Pinus strobus).[152] In the creation story in the Bible, the tree of life and the knowledge of good and evil was planted by God in the Garden of Eden.[153]

Sacred groves exist in China, India, Africa and elsewhere. They are places where the deities live and where all the living things are either sacred or are companions of the gods. Folklore lays down the supernatural penalties that will result if desecration takes place for example by the felling of trees. Because of their protected status, sacred groves may be the only relicts of ancient forest and have a biodiversity much greater than the surrounding area.[154] Some Ancient Indian tree deities, such as Puliyidaivalaiyamman, the Tamil deity of the tamarind tree, or Kadambariyamman, associated with the kadamba tree were seen as manifestations of a goddess who offers her blessings by giving fruits in abundance.[155]

Superlative trees

Main article: List of superlative trees

Trees have a theoretical maximum height of 130 m (430 ft), but the tallest known specimen on earth is believed to be a coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) at Redwood National Park, California. It has been named Hyperion and is 115.6 metres (379 ft) tall.[156] The tallest known broad-leaved tree is a mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) growing in Tasmania with a height of 99.8 m (327 ft).[157]

The largest tree by volume is believed to be a giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) known as the General Sherman Tree in the Sequoia National Park in Tulare County, California. Only the trunk is used in the calculation and the volume is estimated to be 1,487 m3 (52,500 cu ft).[158]

The oldest living tree with a verified age is also in California. It is a Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) growing in the White Mountains. It has been dated by drilling a core sample and counting the annual rings. It is estimated to currently be 5,066 years old.[a][159]

A little further south, at Santa Maria del Tule, Oaxaca, Mexico, is the tree with the broadest trunk. It is a Montezuma cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) known as Árbol del Tule and its diameter at breast height is 11.62 m (38.1 ft) giving it a girth of 36.2 m (119 ft). The tree's trunk is far from round and the exact dimensions may be misleading as the circumference includes much empty space between the large buttress roots.[160]

ශාක

විකිපීඩියා, නිදහස් විශ්වකෝෂය වෙතින්

වෙනත් භාවිතා සඳහා, ශාක (වක්රෝත්තිහරණය) බලන්න.

| Plants Temporal range: Early Cambrian to recent, but see text, 520–0 Ma |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

Domain: |

Eukaryota |

(unranked): |

Archaeplastida |

Kingdom: |

PlantaeHaeckel, 1866[1] |

| Divisions | |

Green algaeLand plants (embryophytes)

†Nematophytes |

|

ශාක යනු ජිවයෙහි විශේෂ ආකාරයක් වන අතර ඒ සඳහා පදුරු, තෘණ වර්ග, පර්නාංග, හරිත ඇල්ගි, පෙද වර්ග, වැල් වර්ග සහ ඖෂධ පැලෑටි අයත්වෙයි. 350000 ප්රමාණයක ශාක විශේෂ ප්රමාණයක් ඇතැයි මේ වන විට ගණන් බලා ඇත. ඒවා බීජ ශාක, bryophyte සහ පර්නාංග වේ. 2004 දී සොයා ගෙන ඇති ආකාරයට 287,655 ප්රමාණයක් විශේෂ හඳුනාගෙන ඇති අතර ඉන් 258,650 ප්රමාණයක් මල් හට ගන්නා ශාක වන අතර 15,000 ප්රමාණයක් bryophyte වේ. හරිත ශාක ඇතැම් අවස්ථාවලදී metaphytes ලෙස හැඳින්වෙන අතර ප්රභාසංස්ලේෂණය මගින් සුර්යය ශක්තිය තිර කරනු ලබති.

පටුන

[සඟවන්න]

වර්ධනය[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

ශාකයක් සෑදී ඇති ඝණ ද්රව්යවලින් වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් ලබාගෙන ඇත්තේ වායුගෝලයෙනි. ඒ ප්රභාසංශ්ලේෂණය නම් වූ ක්රියාවලිය හරහාය. ශාක හිරු එළියෙන් ශක්තිය ලබාගෙන වායු ගෝලයෙන් ලබාගත් CO2 සරල සීනි බවට පත් කරයි. මෙම සීනි එහිදී ගොඩනැංවීමේ කොටස් සේ එකතු වී ශාකයේ ප්රධාන ව්යුහමය සංරචක ගොඩ නංවනු ලබයි. ශාක පස කෙරෙහි ප්රාථමික විශ්වාසය රඳවා ආධාරය සහ (ප්රමාණාත්මක වශයෙන්) ජලය ලබා ගනී. නයිට්රජන්, පොස්පරස් සහ අනෙකුත් තීරණාත්මක පෝෂක මූල ද්රව්ය පසේත් අඩංගුවේ.

බොහෝ ශාකවල සාර්ථක වර්ධනය සඳහා ඒවාට වායුගෝලීය ඔක්සිජන් ශ්වසනය සඳහාද මූල පද්ධතිය වටා ඇති ඔක්සිජන් ද අවශ්ය වේ. කෙසේ වෙතත් විශේෂිත සනාල පැලෑටි කිහිපයක් (කඩොලාන ශාක වැනි)මූල මණ්ඩලය අවට ඔක්සිජන් හීන වූ පරිසරවල වර්ධනය වේ.

අර්ථ දැක්වීම[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

ඇරිස්ටෝටල් විසින් සියළුම ජීවි ද්රව්ය ශාක (සංචරනය කල නොහැකි) සහ සත්ව (සංචරනය කල හැකි සහ ආහාර ද්රව්ය සොයා ගමන් කල හැකි) ලෙස කොටස් දෙකකට බෙදන ලදී. ලිනේයස්ගේ වර්ගි කරණයේදී ඔහු මේවා ශාක (Metaphyta හෝ Plantae) සහ සත්ව (Metazoa) රාජධානි ලෙසද වර්ගි කරණය කරන ලදී. එතැන් පටන් ශාක රාජධානිය විවිධ ඒහා අදාල නොවන කාණ්ඩ සමගද සම්බන්ධ බවට තොරතුරු අනාවරණය වුණි. ඒවා නම් දිලීර වර්ග සහ ඇතැම් ඇල්ගි විශේෂයි. මේවා පසුකාලීනව අලුත් රාජධානියකට වෙන්කර හරින ලදී. කෙසේ නමුත් මේවා බොහෝ අවස්ථා වලදී තව දුරටත් ශාක රාජධානියට අන්තර්ගත ලෙස සලකනු ලැබේ.

ශාක යන නාමකරණය යම්කිසි විශේෂ අවස්ථාවකදී යොදා ගත හොත් එය සාමාන්යයෙන් එකි වර්ග තුනෙන් එකකට අයත්වේ. කුඩාම සිට විශාලතම අවස්ථාව දක්වා මෙකි වර්ගිකරණයන් තුල පහත පරිදි වේ. • ගොඩබිමෙහි ඇති ශාක - මේවා Embryophyta හෝ Metaphyta ලෙසද හැදින්වේ. කුඩාම ශාක වර්ගීකරණ කුලකය පහතින් නිරූපණය කර ඇත. • හරිත ශාක - මේවා Viridiplantae, Viridiphyta හෝ Chlorobionta ලෙසද නම් කෙරෙන අතර ඉහතින් සදහන් කරන ලද Embryophyta, Charophyta සහ Chlorophyta (කොළ පැහැ ඇල්ගි වර්ග) වර්ගයට අයත්වෙයි. • Archaeplastida මේවා ශාක sensu lato ලෙසද හැදින්වේ. Plastida හෝ Primoplantae වලට ඉහති කී කොළ පැහැති ශාක අන්තර් ගත වන අතර Rhodophyta (රතු ඇල්ගි) සහ Glaucophyta වන්ද අයත්වෙයි. පුළුල්ම ශාක වර්ගි කරණයේදී මෙහි බොහෝමයක් වු සුනෂ්ටිකයෙන් අන්තර්ගත වන අතර ඒවා ඔවුන්ගේ chloroplast ලබාගෙන ඇත්තේ සයනෝ බැක්ටිරීයාවන් භක්ෂණය කිරීමෙනි.

වෙනත් ආකාරයකින් කිවහොත් ප්රභාසංස්ලේෂණය සිදු කරන වෙනත් ජිවීන්ද ශාක ලෙස හැදින්වෙන අතර ඒවා සම්ප්රදායික වර්ගිකරණයට අන්තර්ගත නොවන අතර ඔවුන් සැබෑ ශාක වලට සමීප සම්බන්ධතාවයක් නොපවත්වයි. ශාක විශේෂ 375000 ප්රමාණයක් සොයා ගෙන ඇති අතර සෑම වසරකදීම අළුතින් ශාක විශේෂ කිහිපයක් සොයා ගන්නා අතර ඒ පිළිබඳව විග්රහ කරනු ලබයි.

ඇල්ගී[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

බොහෝ ඇල්ගි වර්ග ශාක රාජධානිය යටතට වර්ගිකරණය නොකෙරේ. ඇල්ගි වර්ග විවිධ කාණ්ඩ වලට අයත් ඇල්ගි වර්ග ප්රභාසංස්ලේශණය මගින් ශක්තිය නිපදවන ජීවින් විශේෂ වේ. මින් එක් එක් ඇල්ගි විශේෂ ප්රභාසංස්ලේශණය නොකරන වෙනස් පුර්වජයින්ගෙන් පැවත එයි. මෙම ඇල්ගි අතුරෙන් වඩාත් පැහැදිලි විශේෂය වනුයේ ශාක සමුද්ර විශේෂයි. මොවුන් බහු සෛලික ඇල්ගි විශේෂ වන අතර දළ වශයෙන් භෞමික ශාක වලට සමානකම් දක්වයි. නමුත් මේවා කොළ, රතු සහ දුඹුරු ඇල්ගි ලෙසට වර්ගිකරණයක් සිදු කරනු ලබයි. මෙකී එක් එක් ඇල්ගි වර්ගද විවිධ අන්වීක්ෂීය සහ එක් සෛලික විශේෂ ලෙසට වර්ගීකරණය කර ඇත.

ඇල්ගි වර්ග අතරින් වර්ග දෙකක් පමණක් භෞමික ශාක වලට (Emvriophytes) සමීප සම්බන්ධතාවයක් ඇතැයි සැලකේ. මින් මුල්ම කාණ්ඩය වනුයේ Charophyta වන් වන අතර එමගින් embryophyta වන් ඇති වු බවට සැලකේ. Emdryophyte සහ Charophyte යන කාණ්ඩ දෙකෙහි සංකලනයන් හරිත ඇල්ගි වල (Chlorophyta) දක්නට ඇති අතර මෙහි වඩාත් පැහැදිලි නොවු කාණ්ඩය එක්ව ගත් කල හරිත ශාක හෝ viridiplantae ලෙසට හැඳින්වේ. ශාක රාජධානිය මෙකි ඒකවංශික වර්ගි කරණයට අයත්වෙයි. හරිත ඇල්ගි වල ඇති යම්යම් වෙනස්කම් හැරුණු කොට ඉහත කී සියළුම වර්ග වල සෛල බිත්ති සෙලියුලෝස් වලින් සැදුම් ලත් අතර හරිත වර්ණක A සහ B අන්තර්ගත හරිතප්රද ඇති අතර ආහාර ද්රව්ය පිෂ්ඨය ලෙස ගබඩා කරනු ලැබේ. ඔවුන් තර්කුවක් නොමැතිව අනුනන විභාජනයට ලක්වන අතර පැතලි මියර සහිත මයිටකොන්ඩ්රියාවන් අන්තර්ගත වේ.

හරිත ශාක වල හරිත ලව පටල දෙකකින් ආස්තරණය වී ඇති අතර එමගින් ඔවුන් සයනෝ බැක්ටිරීයාවන්ගෙන් සම්භවය වී ඇති බවට සාක්ෂි ඇත. මෙය අනෙකුත් ඇල්ගි වර්ග දෙක වන Rhodophyta හෙවත් රතු ඇල්ගි සහ Glaucophyta සදහාද සත්යවේ. මෙම සියළුම කාණ්ඩ තුන සදහා පොදු සම්භවයක් අතැයි විශ්වාස කෙරෙන අතර ඔවුන් Archaeplastida නම් වර්ගිකරණයට යටත් වෙයි. මීට අමතරව බොහෝමයක් අනෙකුත් ඇල්ගි වර්ග (උදා - haterokonts, haptophytes, dinoflagellates සහ euglenids) සදහා ද ආස්තරණ පටල තුනකින් හෝ හතරකින් ආවරණය වු හරිත භක්ෂණය පවතී. ඔවුන් හරිත ශාක වල සමීප ඥාතීන් නොවන අතර එහි හරිත ලව ලබාගෙන ඇත්තේ රක්ෂණය කරන ල හෝ සහජීව චර්යා පෙන්වන ද හරිත හෝ රතු ඇල්ගි වලිනි.

දිලීර[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

දිලීර කලින් ශාක රාජධානියට ඇතුළත්කර තිබුණද, එය තව දුරටත් ශාක ලෙස නොසැලකේ. කළල ශාක සහ ඇල්ගී මෙන් නොව දිලීර ප්රභාසංශ්ලේෂක නොවන අතර මෘතෝපජීවී එනම් අවට පරිසරයේ ඇති ද්රව්ය බිඳ දමා දේහයට උරාගැනීමෙන් ආහාර ලබාගනී.දිලීර ශාක වර්ගයක් නොවන නමුත් අතීතයෙදී ශාක ලෙස සලකා තිබෙන අතර එය උද්භිද විද්යාඥයින්ගේ විෂය ධාරාවට ඇතුළත් යයි සළකා ඇත. දිගුකලක සිට දිලීර පරිණාමිකව ශාකවලට වඩා සතුන්ට සමීපයැයි හඳුනාගෙන තිබිණ.නමුත් ඒවා තවමත් මූලික උද්භිද විද්යා පාඨමාලාවල ගැඹුරින්ම ආවරණය කරන අතර සත්ව විද්යා මූලික පාඨමාලාවලදී එය අනිවාර්ය් නොවේ.බොහෝ දිලීර සෑදී ඇත්තේ දිලීර සූත්රකා ලෙස හඳුන්වන අන්වීක්ෂීය ව්යුහ වලින් වන අතර ඒවා සෛලවලට බෙදී හෝ නොබෙදී හෝ පැවතුනත් සූන්යෂ්ටික න්යෂ්ටිදරයි. දිලීරවල ප්රජනක ව්යුහ වන්නේ ඵලදේහ නොහොත් වඩාත් හුරුපුරුදු ලෙස බිම්මල්ය. මොවුන් කිසිම ප්රභාසංශ්ලේෂක කණ්ඩායමකට අයත් නොවන අතර සතුන්ගේ ළඟම නෑයන්වේ. මේ නිසා දිලීරවලට ඔවුන්ගේම රජධානියක් ඇත.

ව්යුහය, වර්ධනය හා විකසනය[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

ශාකයක් සෑදී ඇති ඝණ ද්රව්යය වලින් වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් ලබාගෙන ඇත්තේ වායුගෝලයෙනි. ඒ ප්රභාසංස්ලේශණය නම් වූ ක්රියාවලිය හරහාය. ශාක හිරු එළියෙන් ශක්තිය ලබාගෙන වායු ගෝලයෙන් ලබාගත් CO2 සරල සීනි බවට පත් කරයි. මෙම සීනි එහිදී ගොඩනැංවීමේ කොටස් සේ එකතු වී ශාකයේ ප්රධාන ව්යුහමය සංරචක ගොඩ නංවනු ලබයි. ශාක පස කෙරෙහි ප්රාථමික විශ්වාසය රඳවා ආධාරය සහ (ප්රමාණාත්මක වශයෙන්) ජලය ලබා ගනී. නයිට්රජන්, පොස්පරස් සහ අනෙකුත් තීරණාත්මක පෝෂණ මූල ද්රව්ය පසේත්අඩංගුවේ.

බොහෝ ශාකවල සාර්ථක වර්ධනය සඳහා ඒවාට වායුගෝලීය ඔක්සිජන් ශ්වසනය සඳහා මූල පද්ධතිය වටා ඔනක්සිජන් ද අවශ්ය වේ. කෙෙස් වෙතත් විශේෂිත සනාල පැලෑටි කිහිපයක් (කඩොලාන ශාක වැනි)මූල මණ්ඩලය අවට ඔක්සිජන් හීන වූ පරිසරවලද වර්ධනය වේ .

පාරිසරික විද්යාවට අනුව ශාකවල වැදගත්කම[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

මිනිසා විසින් ප්රයෝජනයට ගන්නා ශාක පිළිබඳව අධ්යයනය කිරීම ආර්ථික උද්භිද විද්යාව හෙවත් මානවවංශ උද්භිත විද්යාව ලෙස හැඳින්වේ.මේවා බොහෝවිට සමානාර්ථපද ලෙස භාවිත කළත්, ඇතැමුන් ආර්ථික උද්භිත විද්යාව ප්රධාන වශයෙන් නවීන වගාකල ශාක පිළිබඳ මානව වංශ උද්භිද විද්යා අධ්යයනයන් පාරම්පරික ශාක වර්ග දේශීය ජනයා විසින් භාවිත කිරීම පිළිබඳ යොමුවී ඇතිබව සලකනු ලබයි.මානවයා විසින් ශාක වගාකිරීම මිනිස් ශිෂ්ටාචාරයේ පදනම වූ කෘෂිකර්මයෙහි කොටසකි.ශාක කෘෂිකර්මය,සත්ත්ව විද්යාව, උද්යාන පාලනය හා වන විද්යාව ලෙස කොටස් වලට බෙදී ඇත.

ආහාර අර්ථයෙන් සියළු මානව පෝෂණය කෙළින්ම හෝ වක්රව ගොඩබිම් ශාක මත රඳාපවතී.බොහෝ මානව පෝෂණය ධාන්ය වර්ග විශේෂයෙන් බඩ ඉරිඟු ,තිරිඟු සහ සහල් මත හෝ වෙනත් ප්රධාන ආහාර බෝග වන අර්තාපල් මඤ්ඤොක්කා සහ රනිල මත රඳා පවතී.ශාකවල ආහාරයට ගන්නා වෙනත් කොටස් අතරට පළතුරු, එළවළු, කජු, ඖෂධ, කුළු බඩු සහ ආහාරයට ගතහැකි මල් වර්ග අයත් වේ.ශාක වලින් ලබාගන්නා බීම වර්ග වලට කෝපි,තේ, වයින්, බියර් සහ මධ්යසාර අයත්වේ. ප්රධාන වශයෙන්ම සීනි ලබාගන්නේ උක් සහ බීට් වළිනි. අහාර පිසින තෙල් සහ මාගරින් ලබාගන්නේ බඩඉරිඟු, සොයා බෝංචි, කැනෝලා, සැෆ් මල් , සූරියකාන්ත, ඔලිව් සහ වෙනත් ශාක වලින්ය.අහාර ආකලන වලට ගම් ඇරබික්, ගුවාගම්, ලොඅකස්ට් බෝංචි ගම්, පිෂ්ඨය සහ පෙක්ටීන් අයත් වේ.

ආහාර නොවන නිෂ්පාදන[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

ගොඩනැගිලි තැනීමට දැව,ලී බඩු,කඩදාසි,කාඩ්බෝඩ්,සංගීත භාණ්ඩ සහ ක්රීඩාභාණ්ඩ සෑදීමට උපයෝගී කොට ගනී.බොහෝ විට රෙදි සෑදීමට කපු,තණ හෝ සෙලියුලෝස් වලින් වෙන්කරගත් රෙයෝන් සහ ඇසිටේට් වැනි කෘතිම කෙඳි යොදාගනී.ශාකවලින් ලබාගන්නා පුනර්ජනනය කළ හැකි ඉන්ධන වලට දර, පීට් සහ අනෙකුත් ජෛව ඉන්ධන අයත් වේ. ගල් අඟුරු සහ පෙට්රෝලියම් ශාක වලින් ව්යුත්පන්නවූ පොසිල ඉන්ධන වලට අයත් වේ. ශාක වලින් ලබාගන්නා ඖෂධ අතරට ඇස්ප්රීන්, ටැක්සොඅල්, මොර්ෆීන් ,ක්වීනීන්, රෙසර්පින්, කොල්චිසීන්, ඩිජිටාලිස් සහ වින්ක්රිස්ටීන් අයත්වේ. ගින්කෝ, එකිනසියා, ෆීවර්ෆිව් සහ සෙන්ට් ජෝන්ස්වර්ට් වැනි ඖෂධීය පරිපූරක සිය ගණනක් ඇත.ශාක වලින් ලබගන්නා කෘමිනාශක අතරට නිකොටීන්, රොටෙනොඅන්, ස්ට්රිච්නීන් සහ පයිරත්රීන් අයත්වේ. ශාක වලින් ලබගන්නා මත්ද්රව්ය වලට ඕපියම්,කොකේන් සහ මරිජුවනා ඇතුලත්වේ. ශාක වලින් ගන්නා විශ අතරට රිසීන්, හෙම්ලොක් ක්යුරෙයා අයත්ය.ශාක කෙඳි වර්ග ,සුගන්ධ තෙල්, ඩයි වර්ග, වර්ණක ,ඉටිවර්ග, ටැනින්, ගස් වලින් ගන්නා කිරි වර්ග,ගම්, රෙසින්, ඇල්කොලොයිඩ, ඇම්බර් සහ වල්ක වැනි බොහෝ ස්වාභාවික නිෂ්පාදන වල ප්රභවයන් ශාකවේ.ශාක වලින් නිපදවාගන්නා නිෂ්පාදන අතරට සබන්,ආලේප,ෂැම්පු,සුවඳ විළවුන්, රූපලාවන්ය ද්රවය, ටර්පන්ටයින්,රබර් ,වාර්නිෂ්, ලිහිසි තෙල්,ලිනොලියම්, ප්ලාස්ටික්,තීන්ත,චුයින්ගම්, සහ හණ කඹ අයත් වේ.අපරිමිත ප්රමාණයක්වූ කාර්මිකව නිපදවන කාබනික රසායන ද්රව්ය වල,මූලික රසායනික ද්රව්යවල ප්රාථමික ප්රභවය වන්නේද ශාකය මෙම රසායනික ද්රව්ය විශාල විවිධත්වයකින් යුතු පර්යේෂණ හා අධ්යයනයන්ට උපයෝගීකොට ගනී.

ශාක කොටස්වල සෞන්දර්යාත්මක ප්රයෝජන[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

දහස් ගණන් ශාක විශේෂ මිනිසාගේ අවට පරිසරය අලංකාර කිරීමට වගාකරනු ලබන අතර ඒවා සෙවණ ලබාදීම, උෂ්ණත්වය අඩුකර ගැනීමට, සුළඟේ වේගය අඩුකර ගැනීමට, ඝෝෂාව අඩුකිරීමට, පෞද්ගලිකත්වය සලසා ගැනීමට සහ පාංශු ඛාදනය වලක්වා ගැනීම ආදියටද යොදාගනී.මිනිසුන් කැපූමල්, වේලන ලද මල් සහ ගෘහාශ්රිත ශාක වර්ග ගෘහස්ථව ප්රයෝජනයට ගනී.එළිමහනේදී ඔවුන් තණකොළ පිට්ටනි සැදීම සඳහා තණකොළ , සෙවණ ලබාදෙන ගස්, අලංකරණය සඳහා වූ ගස් වර්ග.පඳුරු , වැල් ,පළාවර්ගයට අයත් බහුවාර්ෂිකයෝ සහ පාත්තිවලට යොදාගන්නා ශාක ආදිය ප්රයෝජනයට ගනී.ශාකවල අනුරූ බොහෝ විට චිත්ර කලාව ,ගෘහ නිර්මාණ ශිල්පය , රසවින්ධනය,භාෂාව සහ ඡායාරූපකරණයට සහ රෙදිපිළිමත මුදල් ,මුද්දර, කොඩිමත හා වංශවතුන්ගේ ලාංඡන ලෙසද යොදාගනී.ජීවී ශාක කලාවට යොදාගන්නා ක්රම අතරට පඳුරු නොයෙක් හැඩ වලට කැපීම, බොන්සායි, ඉකෙබානා සහ විවිධ ආධාරක මත වැවීම අයත් වේ.අලංකාර ශාක ටියුලිප් මේනියාවේදී මෙන් ඇතැම් විට ඉතිහාසයේ ගමන් මඟ වෙනස්කර ඇත.සංචාරක ව්යාපාරයේදී ශාක වර්ෂයකට ඩොලර් බිලියන ගණනින් ලබාදෙන පදනම වී ඇත්තේ වෘක්ෂ උද්යාන, උද්භිද උද්යාන, ඓතිහාසික උද්යාන, වන උද්යාන, ටියුලිප් සැණකෙළි, වැසිවනාන්තර,වර්ණවත් ශරත් පත්ර ඇති වනාන්තර සහ සකුරා මල් පිපෙන කාලයට පවත්වන සැණකෙළි ආදියට සංචාරකයන් අකර්ශනය වන නිසාය.වීනස් ෆ්ලයිට්රැප් සංවේදී ශාකය සහ පුනර්ජීවන ශාකය ආදිය ඒවායේ අපූරුබව නිසා විකිණුන ශාකවලට උදාහරණයන්ය.

ශාකවල විද්යාත්මක සහ සංස්කෘතිකමය ප්රයෝජන[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

වෘක්ෂවල වර්ධක වළලු පුරා විද්යාවේදී කාළ නිර්ණය සඳහා සහ අතීතයේ පැවැති දේශගුණය පිළිබඳව දැනගැනීම සඳහා වූ වැදගත් ක්රමයකි. මූලික ජීව විද්යාත්මක පර්යෙෂණ ශාක යොදාගෙන සිදුකර ඇත.උදාහරණයක් ලෙස ජාන විද්යාවේ ග්රෙගරි මෙන්ඩල්ගේ නීතිය සොයාගෙන ඇත්තේ පී ශාක උපයෝගී කොටගෙනය. අභ්යවකාශ නැවතුම් පොළවල්,අභ්යවකාශ ජනපද යම් දිනක ජීවිතය රැකගැනීමට ශාකමත විශ්වාසය තබනු ඇත.ශාක ජාතික හා ජනපද ලාංඡන ලෙස යොදාගන්නා අතර එයට ජනපද පුෂ්පය, ජනපද ගස ඇතුලත් වේ. ඓතිහාසිකව වෘක්ෂවලට ගරුකරනු ලබන අතර බොහෝ ඒවා ජනප්රියය.ශාක විසින් ලෝක වර්තා ගණනාවක්ම දරනු ලැබේ.සිහිවටන ත්යාග සහ උපත්, මරණ,විවාහ සහ නිවාඩු දින සැමරීමට ශාක සිටුවනු ලැබේ.ශාක පුරාණ ප්රවාද වල ,ආගම් වල සහ සාහිත්යයේ ප්රමුඛ ස්ථානයක් ගනී. මානව උද්භිද විද්යා ක්ෂේත්රයේ පාරම්පරික සංස්කෘතීන් ශාක භාවිතා කල ආකාරය අධ්යයනය කරන අතර එය තර්ජනයට ලක්වූ ශාක සංරක්ෂණයට සහ නව ඖෂදීය ශාක සොයා ගැනීමට උපකාරී වේ. උද්යාන කරණය එක්සත් ජනපදයේ වඩාත්ම ජනප්රියයි. එරට විවේක කාලයට කරන ක්රියකාරකම නම් ශාක සිටුවීමයි.ශාක සමඟ වැඩකිරීම හෙවත් උද්යාන විද්යා චිකිත්සාව දියවැඩියා රෝගීන් පුනරුප්ථාපනය කිරීමට උපකාරී වේ. දුම්කොළ ,මරිජුවානා සහ ඕපියම් වැනි ශාක මානසික තත්වයට බලපාන රසායන ද්රව්ය වනඅතර ඒවා නිස්සාරණය කරගනී.

ශාකවල සෘණාත්මක බලපෑම[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

වල් පැළෑටි යනු මිනිසාට අනවශ්ය ස්ථාන වල වැඩෙන ශාකයන්ය.මිනිසුන් විසින් ශාක ඔවුන්ගේ උපන් භූමියට වඩා බොහෝ ඈත ප්රදේශ වලට පතුරුවාහරිනු ලබන අතර මෙසේ හඳුන්වාදුන් ශාකවලින් සමහරක් ආක්රමණකාරී ශාක බවට පත්ව දේශීය විශේෂ ඉවත්කරමින් පවතින පරිසර පද්ධතියට හානි සිදුකරයි.ආක්රමණකාරී ශාක විසින් වගාකල බෝග වර්ග විස්ථාපනය කිරීම නිසා වාර්ෂිකව ඩොලර් මිලියන ගණනින් පාඩු සිදුවේ.ඒවා නිෂ්පාදන වියදම ඉහල දමන අතර විනාශ කිරීමට රසායන ද්රව්ය භාවිතාකිරීමෙන් පරිසරයට බලපෑම් එල්ලවේ.

පැළෑටි මිනිසාටද හානිදායක වේ. ශාක විසින් නිපදවන සුලඟේ පාවී යන පරාග නිසා පීනස් රෝගීන් හට ආසාත්මිකත ඇතිවේ. විෂ සහිත ශාක වර්ග පුළුළ් විවිධත්වයකින් පැතිර ඇත.විෂ සහිත අයිවි වැනි ශාක වර්ග සමෙහි ගැටුන විට කැසීම් ඇතිකරයි. දුම්කොළ, මරිජුවානා, කොකේන් සහ ඕපියම් වැනි ඇතැම් ශාක වල මානසිකත්වයට බලපාන රසායන ද්රව්ය උකහා ගැනීම හෝ දුම් පානයෙන් සෞඛ්යට හානි සිදුවේ. එමෙන්ම මරණය පවා සිදුවේ.ශාක වලින් උපදවාගන්නා නීත්යානුකූල හෝ නීත්යානුකූල නොවන මත්ද්රව්ය ආර්ථිකය කෙරෙහි සෘණාත්මකව බලපාන අතර එය වැඩකරන්නාගේ නිෂ්පාදිත ධාරිතාව හා බලාත්මක කිරීමේ වියදම් අඩුකිරීම කෙරෙහි බලපායි.ඇතැම් ශාක වර්ග ශරීරයට උකහාගත් විට මිනිසාට හා සතුන්ට ආසාත්මික ප්රතික්රියා ඇතිකරන අතර තවත් ශාක ආහාර අපත්ය වීමක් ඇතිකරයි.එය සෘණාත්මක සෞඛ්ය බලපෑමකි.

මූලාශ්ර[සංස්කරණය කරන්න]

-

↑ Haeckel G (1866). Generale Morphologie der Organismen. Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer. පිටු vol.1: i–xxxii, 1–574, pls I–II; vol. 2: i–clx, 1–462, pls I–VIII.

ரம்

கட்டற்ற கலைக்களஞ்சியமான விக்கிப்பீடியாவில் இருந்து.

இந்தக் கட்டுரையில் உசாத்துணைகள் இல்லை. |

இக்கட்டுரை தமிழாக்கம் செய்யப்பட வேண்டியுள்ளது. இதைத் தொகுத்துத் தமிழாக்கம் செய்வதன் மூலம் நீங்கள் இதன் வளர்ச்சியில் பங்களிக்கலாம். |

மரம் என்பதை அளவிற் பெரிய பல்லாண்டுத் தாவரம் என வரைவிலக்கணம் கூறலாம். இது நிலத்தில் (ஒரு விதையிலிருந்து) தோன்றி, இடம் விட்டு இடம் தானே நகராது, நிலைத்து வளரக்கூடிய ஒரு நிலைத்திணை வகை ஆகும். இதற்கான அளவு குறித்த வரையறை எதுவும் கூறப்படாவிடினும், பொதுவாக முதிர்ந்த நிலையில் 4.5 மீட்டர் (15 அடி) உயரமும், ஒரு தனி அடிமரத்தில் தாங்கப்பட்ட கிளைகளையும் கொண்டிருக்கும். மரங்கள், இயற்கை நிலத்தோற்றத்தில் முக்கியமான அம்சமாக இருப்பதுடன் நிலத்தோற்றக்கலையில் ஒரு முக்கியமான கூறுமாகும். ஏனைய வகைகளைச் சேர்ந்த செடிகொடி போன்ற நிலத்திணை வகைகளை விட, மரங்கள் நீண்டகாலம் வாழக்கூடியவை. சிலவகை மரங்கள் 100 மீ. (300 அடி), உயரம் வரை வளரக்கூடியவை, சில ஈராயிரம் ஆயிரம் ஆண்டுகளுக்கு மேலும் வாழக்கூடியவை. அமெரிக்காவில் உள்ள கலிபோர்னியா மாநிலத்தில் உள்ள செம்மரம் என்னும் வகை இப்படிப்பட்டன. இதே போல தமிழ் நாட்டில் தூத்துக்குடி மாவட்டத்தில் குலசேகர பட்டினம் என்னும் ஊரில் கடற்கரை அருகில் அமைந்துள்ள ஆப்பிரிக்காவை பூர்வீகமாக கொண்ட "பவோபாப் மரம்" இன்றும் ஆயிரம் ஆண்டுகளை கடந்து வாழ்ந்துகொண்டு இருக்கிறது..

இந்த மரம் தமிழர்கள் ஆதிகாலத்தில் கடல் வணிகத்தில் உலகின் முன்னோடிகளாக இருந்தனர் என்பதற்கு நல்ல உதாரணமாக கூறலாம்..

காரணம் தமிழர்கள் ஆபிரிக்க நாடுகளுக்கு கப்பல் வழி வணிகம் செய்ய போகும்போது இந்த மரத்தின் விதைகளை அங்கிருந்து எடுத்து வந்து இங்கு விதைத்து இருகின்றனர்..

பொருளடக்கம்

[மறை]

உருவவியல் (Morphology)[தொகு]

வேர்கள், அடிமரம், கிளைகள், சிறுகிளைகள், இலைகள் என்பவை மரத்தின் பகுதிகளாகும். மரத் தண்டு, தாங்குவதற்கானதும், நீர், உணவு முதலியவற்றைக் கடத்துவதற்குமான மென்சவ்வுகளைக் (காழ் (xylem) மற்றும் உரியம் (phloem)) கொண்டது. மரம் (மூலப்பொருள்), காழ்க் கலங்களைக் கொண்டது, மரப்பட்டை முக்கியமாக உரியங்களால் ஆனது. மரம் வளரும்போது இது ஆண்டு வளையங்களை உருவாக்குகின்றது. மிதவெப்ப மண்டலக் (temperate) காலநிலைப் பிரதேசங்களில் இந்த வளையங்களை எண்ணுவதன் மூலம் மரத்தின் வயதைக் கணிக்க முடியும். மரத்தின் வேர்கள் பெரும்பாலும் நிலத்திற்கடியிலேயே காணப்படும். இவை மரம் நிலத்தைப் பற்றிப் பிடித்துக்கொள்ள உதவுவதுடன், மண்ணிலிருந்து நீர் மற்றும் போஷாக்குப் பொருட்களை உறிஞ்சவும் பயன்படுகின்றன. தாவரங்கள் உணவைத் தயாரிப்பதற்குச் சூரிய ஒளி தேவை. இலைகளின் மூலமே இச் செயற்பாடு நடைபெறுகின்றது. மரங்கள் அடர்த்தியாகவுள்ள இடங்களில் ஒளிக்காக மற்றத் தாவரங்களுடன், போட்டியிடவேண்டியுள்ளது. இதற்கு உதவும்பொருட்டுத், தண்டுகள், இலைகளைக் கொண்டுள்ள கிளைகளை உயரத்தில் வைத்திருக்க உதவுகின்றன. பல தாவரங்களில், இலைகள் கூடிய அளவு சூரிய ஒளியைப் பெறத்தக்கவகையில், கிளைகளின் ஒழுங்கு அமைந்திருக்கும்.

எல்லா மரங்களும் முன் கூறிய பாகங்களைக் கொண்டிருக்க வேண்டுமென்பதில்லை. உதாரணமாகப் பன்னங்கள் கிளைகளைக் கொண்டிருப்பதில்லை. வட அமெரிக்காவில் வளரும் சாகுவாரோ கக்டஸ்களுக்குச் செயற்பாடுள்ள இலைகள் இல்லை. மரப் பன்னங்கள் பட்டைகளைக் கொண்டிருப்பதில்லை. அவற்றின் பருமட்டான வடிவத்தையும், அளவையும், அடிப்படையாக வைத்து இவையனைத்தும் மரங்களாகவே கொள்ளப்படுகின்றன. சில சமயம் அளவே முக்கியமாகக் கருதப்படுகின்றது. பல கிளைகள் அல்லது தண்டுகளுடன் கூடிய, மரத்தைப் போலவே வடிவமுடைய தாவரமொன்று, அளவில் மிகவும் சிறிதாக இருக்கக்கூடும். இது செடியென்று அழைக்கப்படுகின்றது. எனினும் மரத்துக்கும், செடிக்கும் இடையில் சரியான வேறுபடுத்தும் எல்லை கிடையாது. சிறியனவாக இருப்பதால் "பொன்சாய்"கள் மரங்கள் என்று கொள்ளப்படமுடியாது, எனினும் மரவகைகளின் வடிவத்தைக் கருதும்போது, தனியொரு specimen இன் வடிவத்தோடு குழப்பிக்கொள்ளக்கூடாது. மூங்கில்கள் மரங்களின் பல இயல்புகளைக் கொண்டிருந்தாலும், அவை மரங்களென அழைக்கப்படுவதில்லை.

ஒன்றாக வளரும் சிறு கூட்டம் மரங்கள் தோப்பு எனப்படுகின்றன, பெரியதொரு நிலப்பரப்பில் மரங்கள் அடர்ந்திருக்கும்போது அது காடு எனப்படுகின்றது. பெரிய ஆனால் ஐதாக இருக்கும் மரங்களையும் இடையில் புல்வெளிகளையும் (வழக்கமாக மேய்ச்சலுக்கு விடப்பட்ட அல்லது எரிக்கப்பட்ட) கொண்ட பகுதி வெப்பப் புல்வெளி (savanna) எனப்படுகின்றது. மேலும்..

முக்கிய மரவகைகள் (genera)[தொகு]

மரங்கள் பல்வேறுபட்ட தாவரக் குடும்பங்களுள் அடங்குகின்றன. அதனால், இவை பல்வேறுவகையான இலை வகைகள், வடிவங்கள், பட்டைகள், பூக்கள், பழங்கள், முதலியவற்றைக் கொண்டவையாக உள்ளன. ஆரம்பகால மரங்கள், பெரிய காடுகளில் வளரும் மரப் பன்னங்களாக இருக்கக்கூடும். பின்னர் ஊசியிலை மரங்கள், கிங்க்கோக்கள், சைக்காட்டுகள் மற்றும் எனைய வித்துமூடியிலிகள் (gymnosperm) போன்றவை தோன்றின. இன்று பெரும்பாலான மரங்கள் பூக்கும் தாவரங்களும், ஊசியிலைத் தாவரங்களுமாகும். கிழேயுள்ள பட்டியல் பெரிதும் அறியப்பட்ட மரங்களின் பெயர்களையும், அவை பொதுவாக எவ்வாறு வகைப்படுத்தப்பட்டுள்ளன என்பதையும் காட்டுகின்றது.

பூக்கும் தாவரங்கள் (Magnoliophyta)[தொகு]

இருவித்திலைத் தாவரங்கள் (Magnoliopsida)[தொகு]

-

அனக்காடியேசியே (மரமுந்திரி குடும்பம்)

-

மரமுந்திரி, அனக்காடியம் ஒக்சிடென்தலே

-

மா, மங்கிபேரா இந்திகா

-

பசுங்கொட்டை, பிஸ்தாசியா வேரா (Pistacia vera)

-

Lacquer tree, டொக்சிகோடென்றன் வேர்ணிசிபு(f)ளூவா (Toxicodendron verniciflua)

-

-

Aquifoliaceae (Holly குடும்பம்)

-

Holly, Ilex வகை

-

-

அரலியேசியே (Ivy குடும்பம்)

-

Kalopanax, கலோபானக்ஸ் பிக்டஸ் (Kalopanax pictus)

-

-

Betulaceae (Birch குடும்பம்)

-

பொ(b)ம்பாகேசியே (பெருக்க மரம் குடும்பம்; sometimes included in மால்வேசியே)

-

பெருக்க மரம், அடன்சோனியா வகை

-

முள்ளிலவு, பொ(b)ம்பா(b)க்ஸ் சீபா(b) (Bombax ceiba)

-

Kapok, சீபா பெண்டந்திரா (Ceiba pentandra)

-

துரியான், துரியோ ஸிபெத்தினஸ் (Durio zibethinus)

-

பல்சா, ஒகுரோமா லகோ(g)பஸ் (Ochroma lagopus)

-

-

பர்சரேசியே

-

கார்வேம்பு, கரூகா பின்னாட்டா (Garuga pinnata)

-

-

கக்டாசியே (கள்ளி குடும்பம்)

-

Saguaro, கார்னேஜியே ஜைஜண்டியா (Carnegiea gigantea)

-

-

கோர்னாசேசியே (Dogwood குடும்பம்)

-

Dogwood, கோர்னஸ் (Cornus) வகை

-

-

கோரிலேசியே (ஹஸெல் குடும்பம்)

-

பா(f)பே(b)சியே (பட்டாணி குடும்பம்)

-

Honey locust, Gleditsia triacanthos

-

Black locust, Robinia pseudoacacia

-

Laburnum, லபூர்னம் (Laburnum) வகை

-

Pau Brasil, Brazilwood, Caesalpinia echinata

-

-

பா(f)கே(g)சியே (பீ(b)ச் குடும்பம் )

-

செசுநட், Castanea வகை

-

பீ(b)ச், Fagus வகை

-

Southern beech, Nothofagus வகை

-

Tanoak, Lithocarpus densiflorus

-

ஓக், Quercus வகை

-

-

Fouquieriaceae (Boojum குடும்பம்)

-

Boojum, போர்குவேரியா கொலம்னாரிஸ் (Fouquieria columnaris)

-

-

Hamamelidaceae (Witch-hazel குடும்பம்)

-

Sweet-gum, லிக்குயிடம்பர் (Liquidambar) வகை

-

Persian ironwood, பரோட்டியா பேர்ஸிக்கா (Parrotia persica)

-

-

ஜக்லண்டேசியே (Walnut குடும்பம்)

-

லோரேசியே (Laurel குடும்பம்)

-

கறுவா சினமோமம் ஸெலனிக்கம் (Cinnamomum zeylanicum)

-

Bay laurel லோரல் நொபிலிஸ் (Laurus nobilis)

-

அவகாடோ பேசியா அமெரிக்கானா (Persea americana)

-

-

லைத்திரேசியே Loosestrife குடும்பம்

-

Crape myrtle Lagerstroemia வகை

-

-

மக்னோலியேசியே (Magnolia குடும்பம்)

-

Tulip tree, Liriodendron species

-

Magnolia, Magnolia வகை

-

-

மல்வேசியே (திலியேசியே உள்ளடங்கியது) (Mallow குடும்பம்.)

-

Linden (Basswood, Lime), Tilia வகை

-

-

மெலியேசியே (மலைவேம்பு குடும்பம்)

-

வேம்பு, Azadirachta indica (A. Juss)

-

Bead tree, மெலியா அஸெடராச் (Melia azedarach)

-

மலை வேம்பு, சுவீதெனியா மககோனி (Swietenia mahagoni)

-

-

மோராசியே

-

மைரிஸ்டிகேசியே (சாதிக்காய் மரம் குடும்பம்)

-

சாதிக்காய் மரம், மைஸ்ரிஸ்டிகா பி(f)ராகிரன்ஸ் (Mysristica fragrans)

-

-

மிர்ட்டேசியே (Myrtle குடும்பம் )

-

யுகலிப்டஸ், யுகலிப்டஸ் வகை

-

Myrtle, Myrtus வகை

-

கொய்யா, சிடியம் குவாஜாவா (Psidium guajava)

-

நாவல், Syzygium cumini

-

-

நைசாசியே (Tupelo குடும்பம்; சிலசமயம் Cornaceaeல் உள்ளடக்கப்படுகின்றது)

-

ஒலியேசியே (ஒலிவ் குடும்பம்)

-

பப்பிலியோனேசியே

-

புங்கை, பொங்கமியா பின்னாட்டா (Pongamia pinnata)

-

முருக்கு, முள்முருக்கு, எரித்ரைனா இந்திக்கா (Erythrina indica)

-

-

பிளாட்டனேசியே (Plane குடும்பம்)

-

Plane, பிளாட்டனஸ் வகை

-

-

ரிஸோபோராசியே (அலையாத்தித் தாவரங்கள் குடும்பம்)

-

Red Mangrove, ரிஸோபோரா மங்கிள் (Rhizophora mangle)

-

-

ரோசேசியே (ரோஜா குடும்பம்)

-

காஃபி குடும்பம் (தாவரவியல்) (Bedstraw குடும்பம்)

-

காப்பி, காபி(f)யா அராபிக்கா

-

-

Rutaceae (Rue குடும்பம்)

-

Salicaceae (Willow குடும்பம்)

-

Sapindaceae (including Aceraceae, Hippocastanaceae) (Soapberry குடும்பம்)

-

மேப்பிள், Acer வகை

-

Buckeye, Horse-chestnut, Aesculus வகை

-

Mexican buckeye, Ungnadia speciosa

-

விளச்சிப்பழம், Litchi sinensis

-

Golden rain tree, Koelreuteria paniculata

-

-

Sapotaceae family

-

Tambalacoque, or dodo tree, Sideroxylon grandiflorum, previously Calvaria major

-

-

Simaroubaceae குடும்பம்

-

Tree of heaven, Ailanthus வகை

-

-

Sterculiaceae குடும்பம்

-

Ulmaceae (Elm குடும்பம்)

ஒருவித்திலைத் தாவரங்கள் (Liliopsida)[தொகு]

-

அகாவேசியே (அகாவே குடும்பம்)

-

Cabbage palm, கோர்டிலைன் அவுஸ்திரேலிஸ் (Cordyline australis)

-

Dragon மரம், ட்றசீனா ட்றாக்கோ (Dracaena draco )

-

Joshua மரம், Yucca brevifolia

-

-

அரெகேசியே (Palmae) (Palm குடும்பம்)

-

கமுகு, அரெக்கா காட்டெச்சு

-

தென்னை கோகோஸ் நியூசிபெ(f)ரா

-

பேரீந்து Palm, Phoenix dactylifera

-

Chusan Palm, Trachycarpus fortunei

-

-

போவாசியே (புல் குடும்பம்)

-

மூங்கில்கள் Poaceae subfamily Bambusoideae

-

-

வாழைகள், மரத்தன்மையற்றதாலும், பல்லாண்டுத் தாவரமல்லாததாலும், உண்மையில் மரங்களல்ல என்பதைக் கவனிக்கவும்.

ஊசியிலை மரங்கள்[தொகு]

-

Araucariaceae (Araucaria குடும்பம்)

-

குப்பிரசாசியே (சைப்பிரஸ் குடும்பம்)

-

சைப்பிரஸ், குப்பிரசெஸ் வகை

-

சைப்பிரஸ், Chamaecyparis வகை

-

Juniper, Juniperus வகை

-

Alerce or Patagonian cypress, Fitzroya cupressoides

-

Sugi, Cryptomeria japonica

-

கலிபோர்னியா செம்மரம், Sequoia sempervirens

-

Giant sequoia, Sequoiadendron giganteum

-

Dawn redwood, Metasequoia glyptostroboides

-

Bald சைப்பிரஸ், Taxodium distichum

-

-

பைனாசியே (பைன் குடும்பம்)

-

வெண் பைன், பைனஸ் வகை

-

Pinyon பைன், பைனஸ் வகை

-

பைன், பைனஸ் வகை

-

Spruce, பீசியா வகை

-

Larch, லாரிக்ஸ் வகை

-

டக்லஸ்-பே(f)ர், Pseudotsuga வகை

-

பே(f)ர், Abies வகை

-

செடார், Cedrus வகை

-

-

Podocarpaceae (Yellow-wood குடும்பம்)

-

African yellow-wood, Afrocarpus falcatus

-

Totara, Podocarpus totara

-

-

Taxaceae (Yew குடும்பம்)

-

Yew, Taxus வகை

-

Ginkgos[தொகு]

சைக்கட்டுகள் (வித்துமூடியிலித் தாவரங்கள்)[தொகு]

-

சைக்கடேசியே குடும்பம்

-

Ngathu சைக்காட், சைக்கஸ் ஆங்கிலாட்டா (Cycas angulata)

-

-

Zamiaceae குடும்பம்

-

Wunu cycad, Lepidozamia hopei

-

பன்னங்கள் (Fern)[தொகு]

-

Cyatheaceae and Dicksoniaceae families

-

மரப் பன்னங்கள், Cyathea, Alsophila, Dicksonia (ஒரு monophyletic கூட்டமல்ல)

-

வாழ்வுக் கட்டங்கள்[தொகு]

மரங்களின், விசேடமாக ஊசியிலை மரங்களின், வாழ்க்கை வட்டம், காடு வளர்ப்புத் துறையில், கணக்கெடுப்பு மற்றும் ஆவணப்படுத்தும் நோக்கங்களுக்காக பின்வரும் கட்டங்களாகப் பிரிக்கப்படுகின்றது:

-

விதை

-

நாற்று: விதையிலிருந்து முளைத்துவரும், முளையத்தின் நிலத்துக்கு மேலுள்ள பகுதி.

-

Sapling: முளையம் வளர்ந்து 1மீ உயரத்திலிருந்து அதன் தண்டு 7 சமீ விட்டமுள்ளதாக ஆகும் வரையுள்ள கட்டம்.

-

Pole: 7 தொடக்கம் 30 சமீ விட்டமுள்ள இளம் மரங்கள்.

-

முதிர்ந்த மரம்: 30 சமீ க்கு மேற்பட்ட விட்டம், இனப்பெருக்கக் காலத்தின் தொடக்கம்.

-

முதிய மரம்: பழைய வளர்ச்சிக் காடுகளில் அதிகம்; உயர வளர்ச்சி பெருமளவு குறைந்துவிடும், அதிகரித்த விதை உற்பத்தி.

-

அளவுமீறிய முதிர்ச்சி: dieback மற்றும் பழுதடைதல் சாதாரணம்.

-

Snag: நிற்கும் இறந்த மரங்கள்

-

மரக்குற்றி/கழிவு: விழுந்த மரக்குற்றிகள்

மரத்தின் விட்டம், அதன் அடியில், நிலத்தின் அதியுயர்ந்த புள்ளியிலிருந்து 1.3 – 1.5 மீட்டர் உயரத்தில் அளக்கப்படுகின்றது. 7 சமீ விட்ட வரையறை பொருளாதார ரீதியிலானது. இதுவே கடதாசி உற்பத்தி போன்றவற்றுக்காக விற்கப்படக்கூடிய அதி குறைந்த விட்டமாகும். 30 சமீ விட்டமே அரியப்படும் மரங்களுக்கான ஆகக்குறைந்த விட்டம். ஒவ்வொரு கட்டமும் may be uniquely perceptive to different pathogens and suitable for especially adapted arboreal animals.

பண்பாடு[தொகு]

மரங்கள் வழக்கமாக பழங்கதைகளிலும், சமயத்திலும் முக்கிய குறியீடுகளாக இருந்துவருகின்றன. உதாரணமாக நோர்ஸ் பழங்கதைகளில்Yggdrasil, ஜெர்மானிக் பழங்கதைகளிலிருந்து பெறப்பட்ட நத்தார் மரம், யூதாயிசத்தினதும், கிறிஸ்துவத்தினதும் அறிவு மரம், பௌத்தத்தின் போதி மரம் மற்றும் இந்துப் பழங்கதைகள் கூறும் கற்பகதரு என்பவற்றைக் கூறலாம்.

பின்வருவனவற்றையும் பார்க்கவும்[தொகு]

Plant

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Plants)

For other uses, see Plant (disambiguation).

For an explanation of similar terms, see Viridiplantae.

| Plants Temporal range: Mesoproterozoic–present |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

Domain: |

Eukaryota |

(unranked): |

Archaeplastida |

Kingdom: |

Plantaesensu Copeland, 1956 |

| Divisions | |

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Plants are mainly multicellular, predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae.

The term is today generally limited to the green plants, which form an unranked clade Viridiplantae (Latin for "green plants"). This includes the flowering plants, conifers and other gymnosperms, ferns, clubmosses, hornworts, liverworts, mosses and the green algae, and excludes the red and brown algae. Historically, plants formed one of two kingdoms covering all living things that weren't animals, and both algae and fungi were treated as plants; however all current definitions of "plant" exclude the fungi and some algae, as well as the prokaryotes (the archaea and bacteria).